Conflict Sensitive Journalism - A Toolbox for High Quality Conflict and Crisis Reporting

In the first post of this short series we took a look at the origins of Conflict Sensitive Journalism and how the concept relates to peace journalism and other approaches to reporting on conflict, crisis and war. In this second post we will explore what Conflict Sensitive Journalism requires in practice. What is it that reporters and editors do differently when they choose to report in a conflict sensitive way - and how does this shift in perspective impact on the conflict situation and its stakeholders?

Journalism requires reporters and editors to make decisions on what to report and how to report it. At first glance these questions seem simple - 'just report the facts' is what young journalists often hear from their teachers and seniors. However, in reality it is rarely this straight forward. Facts aren't independent from our perception of them and therefore, unavoidably, a journalist's reporting is shaped by the journalist's own perspective as well as external pressures and expectations; editorial demands, location and target group of the media outlet, house styles, assumptions of what sells and what doesn’t and countless other rules and habits which have evolved and are seldom questioned in daily practice.

Journalists are too often guided by wild editorial prerogatives: 'What bleeds, that leads!' is a cynical but persistent mantra in news rooms, so is the illusion of objectivity. To find true, meaningful guidance journalists need to go back to the roots of their profession. What and how we report ultimately depends on how we as reporters and editors perceive the task and role of journalism in society, how we look at our readers and audiences and how we as media practitioners relate our stories to current affairs, situations and conditions in society.

In this article I will discuss common habits in media practice that erode the quality of reporting and have led to a reporting style that too often adds fuel to the fire in an already tense situation. These habits aren't caused by journalists being 'bad' but have evolved in response to increasing competition among reporters, market pressure and a growing business orientation of media outlets.

Key Concepts Of Conflict Sensitive Journalism

I will then introduce the key concepts of Conflict Sensitive Journalism which are essential for journalists to achieve high quality reporting of conflict, crisis and war. These concepts are based on a deeper understanding of the dynamics of conflict, lean on the instruments of conflict analysis but are based on a solid foundation of journalism values and principles - and they present a reporting that as such can support de-escalation without forcing journalists into advocacy.

In our work with journalists around the globe we have identified 18 significant principles, shifts in thinking and focus in media reporting that enable us to achieve high quality reporting on conflict. These concepts provide guidance for practicing journalists and have been developed as strategies to overcome the negative habits of the media. They are based on widely agreed journalistic values such as truth, accuracy, balance, impartiality and independence.

I will start with the initial eight principles in this post and then add the remaining ten in the next post. In the final post I'd like to explore further the relationship of journalism with conflict and peace and look at the powerful de-escalating influence high quality reporting can have on conflicts. But now, let's take a look at those first eight principles of Conflict Sensitive Journalism.

Principle I: Be Clear About The Role Of Journalism In Society

Many journalists and media practitioners have a rather cynical perception of their profession. They feel that their media outlets have lost their purpose as a democratic institution, a watch dog that keeps those in power accountable. Instead media has become just another business. The philosopher Noam Chomsky captured this perception in his 'Propaganda Model', where he describes the media as a business that produces readers for its advertisers.

Conflict Sensitive Journalism rejects this gloomy perspective. It embraces a different journalistic ideal wherein journalism is not just a business, but also not only a watch dog. It is a channel for communication in a society too large to allow its members to communicate directly with each other.

This idea which Carsten Broska described in his 'Discursive Journalism Model' represents a slight but significant change in the role of journalism: As a communication channel the media provides more than pre-selected facts. It offers members of society orientation on the ongoing discourse and enables active participation. The journalist as communication channel is much more than just a watch dog that barks up the tree of misconduct; he or she is a conduit for social discourse.

Business oriented media has given up much of its relevance as democratic function in society in exchange for influence, cost efficiency and entertainment. Depriving the people of access to independent, reliable information weakens democracy and the capacity of society to deal with conflicts nonviolently and constructively. Discursive journalism on the other hand opens a communication channel between conflicting parties, a room for exchange and conversation that is not limited by the ability of parties to meet or even their willingness to communicate with each other. Journalism can create communication beyond hard frontiers, a process critical to overcoming violence and engaging in more constructive dialogue and ultimately collaboration.

Principle II: Framing The Conflict: Two-Party Versus Round-Table Geometry

Traditional reporting of conflict tends to fall into a trap of over-simplification. Journalists are acutely aware that their audiences have short attention spans. The news are read over breakfast or on the tablet while commuting to work and most readers want the crucial facts quickly but lack patience with in-depth explanations. The complexity of conflict doesn't sit well in this format. To make the complicated digestible and fit for format - and sometimes constrained by their own limited understanding - journalists tend to over-simplify conflicts, reporting them in a way that Jake Lynch called the 'Two-Party-Geometry'.

Two-Party-Geometry means conflict is seen as dual, with two parties fighting over one goal. Every gain of one party is a loss for the other party. The only possible outcomes are victory or defeat.

Journalists count the wins and losses, focusing on the death toll, territory won or lost and the equipments used by the opponent. The key question in such reports is 'Who will win?'

Describing a conflict as two parties fighting over one goal creates a tug-of-war logic. It leads to escalation by creating competition and blocks collaboration. It also is a failure of accuracy since conflicts are never that simple.

Reporting conflict accurately requires journalists to identify all stakeholders and give all of them equal opportunity to express their perspectives, interests and needs. In Conflict Sensitive Journalism reporters identify the many diverse stakeholders. Instead of aggregating them into two parties journalists explore their unique interests and needs and see each of their contributions as equally important regardless of their status, power or numbers.

By presenting multiple stakeholders’ views media reports become a channel for communication among the various actors in a conflict situation. The reports open a 'Round Table' where each stakeholder has their place and the issues can be laid open to be worked on together. The key questions are 'Who is involved?' and 'What do all these stakeholders really want?'. These questions open up dialogue instead of stressing adversity and contradictions.

Principle III: Exploring Complexity Instead of Simplifying

Whenever journalists simplify by framing a conflict as a 'Two-Party-Geometry' they tie up their readers in a constrained logic of understanding. This logic is dominated by binary thinking and enforces polarization. Dualism and 'Black and White-Thinking', Manichaeism - the idea that there is Good versus Evil - are natural elements of this common conflict logic.

In such a logic direct violence is the result of madness, fanaticism or tribal anarchy. One party (the evil guys) commit atrocities against the other party (the good guys) because they are evil or have lost their sanity. The good guys (us) then have all rights and even obligations to attack the evil ones (them) to remove the threat they represent. That is how an argument for war is built.

To create understanding and facilitate communication as the discursive journalism model requires, reporters have to explore and explain complexity instead of simplifying complex situations. Key questions are: who are the stakeholders? What are the interests behind their positions? What are their motivations?

Journalists need to analyze the conditions and context in which a conflict evolves to identify true explanations for violence. As a result it often becomes apparent that direct violence is explained by structural and cultural violence - not the madness of an evil villain. We'll explore these aspects of violence further later on but let's stay for a moment with the question of simplification versus complexity.

Principle IV: The Goal Of Journalism: Understanding, Not Entertaining

One of the reasons why journalists fall prey to the simplified and violence oriented style of reporting is that too often journalism is seen through the lens of entertainment. Entertainment serves the commercial interests of media and is easier to produce than high-quality reporting, which is why it has taken hold of journalism so effectively - and to the detriment of real quality in reporting.

Where journalism is primarily seen as a business, its products are judged by what creates the biggest possible profit with the smallest necessary investment. Information gathering is more expensive than selling less informative reports via means of entertainment. Instead of investing in often tedious research and investigation and the endless verification of information, such entertainment reporting utilizes the strategies of marketing and storytelling to make “catchy” reports.

As an example, for a media organization oriented towards entertainment, a sensationalist and gory report of a bomb site produced with agency visuals represents higher value than an elaborate investigative report on the origins of the perpetrators and the conditions that make extremist ideologies attractive especially for younger people who see little hope for their future.

The impact of such reports on the reader is very different. Focus on the violent event with no deeper explanation leaves the reader to draw their own conclusions based on biases and assumptions. Where pain seems senselessly inflicted a harsh and equally violent response seems justified. On the other hand, understanding that despair and hopelessness, marginalization and discrimation causespeople to be receptive to extremism and manipulation makes us realize that a harsh response will be less likely to lead to improvement. More likely it will worsen the problem, an effect all of us who have worked in conflict have been able to observe.

The purpose of journalism is not to entertain but to inform and educate the reader. This empowers readers to participate in public discourse by increasing knowledge and providing a platform for discussion. Journalism is not just another business and defining its priorities based on return of investment is not only leading to wrong conclusions and misguided 'solutions'. It undermines democracy as such.

Principle V: Process-Oriented InsTead Of Event-Based Reporting

Let's stay with the example of the report of a bombing for a moment. Whenever a bomb explodes somewhere media reporting tends to show the same pattern: The site is described in more or less detail, the number of deaths and injured is counted and immediate reactions of officials are broadcasted. This is what we describe as 'event-oriented' reporting.

Event-oriented reporting focuses on the immediate event but mostly ignores the event's context. By ignoring past events that have led to this moment such reporting only allows events to be explained by the immediate happenings. The fundamental question 'Why has it happened?' often remains unanswered. This oversimplifies and leads to wrong conclusions and blaming.

Conflict Sensitive Journalism requires reporting to be process-oriented instead of just event-based. Process-oriented reporting includes the history of events, the context, circumstances and conditions (i.e. the dire and desperate living conditions of the perpetrators, discrinimation and marginalization, the loss of loved ones through security forces, militias etc.), and thereby presents the larger picture which allows the reader to understand why an event happened.

This is especially critical when an event involves violence. Events involving direct violence are explained by the circumstances created by structural and cultural violence. Failure to explore this background means the reader fills the gap of information. And while lacking relevant explanations will assume the perpetrators were evil, insane or their ethnicity or religion caused them to act violently. A conclusion that is not only wrong in most cases but also leads to a deteriorating relationship between conflict parties.

Principle VI: Where There Is Direct Violence There is Structural and Cultural Violence

How to report violence is a critical challenge for Conflict Sensitive Journalism. When it comes to reporting violence traditional reports most often focus exclusively on direct violence, the visible, physical attack. They identify the perpetrators, stress gory details and provide graphic descriptions. Violence is seen and used as entertainment or emotional shock treatment. Readers react emotionally and with anger against the perpetrators which demonizes the perpetrators and thereby justifies a “tough” response (e.g. military crackdown).

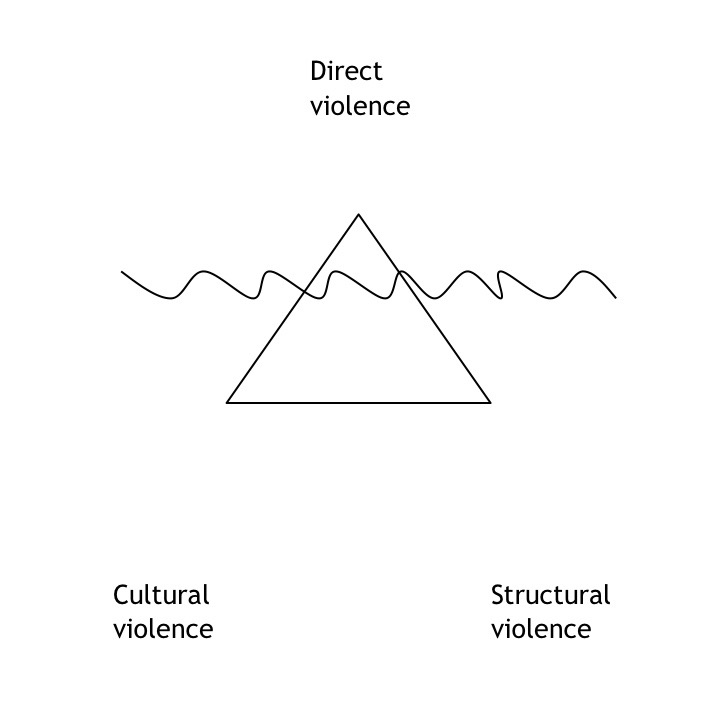

However, violence is not just the direct, physical, destructive act. Johan Galtung has developed a concept that takes a broader look at violence not just as an act of individuals but as a social construct.

Here is a brief recap of the concept:

Where there is direct violence, atrocities committed by one person or group against another, there is always also structural and cultural violence. Structural violence is embedded in the systems and structures of a society, it's laws, it's processes to deliver justice. Cultural violence is embedded in the believes and values of a community.

E.g. in the United States people of colour are still perceived as less able to be successful and more likely to be criminals (cultural violence), they are more likely to be convicted and sent to prison than white people when in front of a judge and face longer sentences (structural violence) and police have repeatedly shot and killed people of colour they felt posed a threat (direct violence). These three aspects of violence are connected and reinforce each other, as Johan Galtung has explained in his Triangle of Violence framework.

Journalists' reports need to identify and explain structural and cultural violence. Only by bringing these to the surface our readers can gain a deeper understanding of the root causes of violence; e.g. poverty, discrimination, marginalization, loss etc. Understanding these conditions does not serve as justification for violence but allows the reader to recognize the real problems. And as mentioned earlier, this may lead to the revelation that a “tough” response often does not make sense because it does not reduce but rather increases the violence (discrimination is not addressed by declaring martial law, poverty cannot be reduced by a military crackdown).

Principle VII: Exploring Interests Behind Positions

When journalists report about conflicts a significant amount of the reporting is focused on interviews with leaders and politicians. These interviewees give us their carefully phrased statements designed to support their particular claims and demands and discredit their 'enemies'. War has become the battlefield of PR agencies.

Journalists in their reports usually focus on what the parties say what they want. These are the positions of the conflict parties. Positions are often mutually exclusive (only one party can have the land, the money etc) because they are designed to enforce a parties demands.

If we focus on mutually exclusive positions the only way for a party to get what they want is to win. In such a logic victory or defeat are the only possible outcomes. Since defeat is unacceptable this leads to increasing competition between parties and an escalation of the conflict. Collaboration is not possible and the best possible outcome is a settlement based on a compromise - which is, however, still a win-lose outcome.

The concept of mutually exclusive “wants” is stressed by two party geometry and builds up the logic of a zero-sum game, in which each gain for one side is automatically considered a loss for the other side.

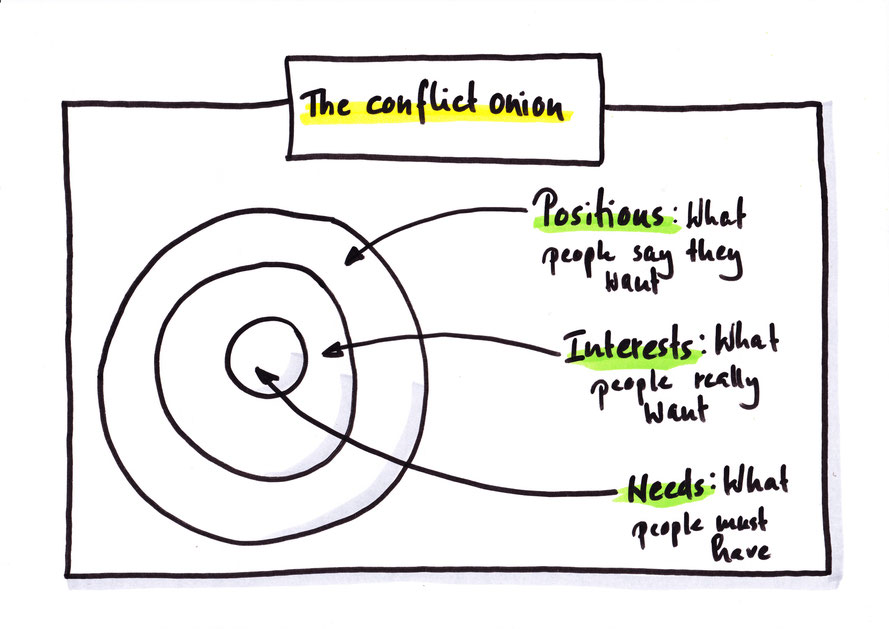

The desires of stakeholders in a conflict situation are multilayered like an onion.

The outer layer represents the positions, the demands parties openly express, packaged to strengthen and justify their claim (e.g. the land is mine, it has to be given back to me because I have the written land title). Behind those positions, however, are interests. Interests describe what the parties really want (e.g. a safe, cheap and beautiful place to bring up children and enjoy retirement). Interests are built on the parties needs (e.g. safety, income, comfort etc). Needs are fundamental and drive the parties actions. Interests and needs are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Therefore all parties can achieve their interests without the other parties having to “pay”, which is described with the term positive sum game.

Conflict Sensitive Journalism requires journalists to look behind the positions, behind what the stakeholders in conflict say what they want and explore their underlying interest and needs. This opens up room for mutual understanding and at some point hopefully collaboration.

Principle 8: From An Elite-Oriented To A People-Oriented Reporting

Have you ever wondered why so much focus in the news media is given to perceived leaders? Probably not, and neither have most journalists. It is an unquestioned assumption that elites are more newsworthy than Joe or Jane down the road. Elite news makers receive primary attention based on their news value of prominence. Elite sources, which are still mostly male, white and middle-aged, are seen as representatives of the people, their “mouth piece”, even when they are not elected officials.

In the news 'normal' people receive attention if they become victims or perpetrators or subjects of a human interest story where they gain news value because there is blood, crime, emotions and tragedy. The problem with this journalistic selection is that it disempowers the readers. It suggests that people are generally passive, at the receiving end of history not where it is made, and therefore have to wait and hope that their leaders will make good decisions for them.

This is of course not an accurate reflection of reality. The most powerful movements have been started not by elites but by regular people who had enough of waiting for their leaders to make change happen. And journalists have to recognize this.

In Conflict Sensitive Journalism news value is seen through the lens of relevance. Elite news makers receive attention if their statements have impact on and are therefore relevant to the story and so do non-elite sources and news makers. Reporting does not focus on distinguishing between victims and perpetrators, elites and people, combatants and non-combatants - you may recognize the two-party geometry here.

Instead Conflict Sensitive Reporting looks at each stakeholder and person individually, humanizing all involved, aiming at understanding their perspective, identifying their interests and needs. Each group is given the chance to speak for themselves; e.g. a group of farmers is represented by a farmer and not by the local mayor or an charity worker. This includes men, women, and everyone in-between, the aged, children etc.

Relevant and balanced journalism defines the value of a source or statement solely by the relevance of that respective group, person or opinion for the story. Reporting is geared towards integrating a variety of perspectives. The reporter does not decide to either report elite perspectives or people perspectives but aims to include both presented by various stakeholders.

This requires to find sources who truly represent each of the actors, and involves also minority or underprivileged groups and individuals. It might be the most underestimated source which provides the most interesting insight.

To Be Continued

I will take a break here and continue this list of critical shifts in journalism reporting in my next post. Meanwhile I leave you to relate these concepts to your own experiences working in conflict or in journalism.

The concept described here are all developed with insights from researchers, conflict workers and practicing journalists around the globe - people like you and me. They bring together the understanding of conflict that peacebuilding practitioners have gained throughout decades in the field and the equivalent deep knowledge and values frameworks that serve as foundation of journalism. Conflict Sensitive Journalism tries to bring both of these worlds together to create a reporting that empowers, enables and nurtures human societies and helps us to overcome the horrors of war and learn to solve conflicts non-violently.

Guest post by Antonia Koop.