Power and peacebuilding

Following from the last blog post on power and violence, we can start from a shared view that peacebuilding challenges the abuse of power. We have noted that technical implementation of programmes, or the dissemination of information, awareness raising or negotiating an accommodation between two violent opponents may all contribute to peacebuilding, but if they do not address issues of power then they do not go to the source of violence.

We also observed that, by contrast, the most prominent and inspiring peacebuilders of the past century have all challenged violence, and addressed the abuse of power. Few would contest that the might of the British Empire in India, or of the Apartheid regime in South Africa, were overthrown principally by the power of non-violence. In order to change power relations and challenge the powerful, peacebuilders must use means more effective then their opponents.

I use the word ‘opponents’ deliberately. When peacebuilders address power and seek to change power relations, they will have powerful opponents. It is quite wrong to pretend that peacebuilding is about being friendly to powerful people, or giving them information that will cause them to consider their behaviour, and thereby reform. Certainly such actions can be positive and such responses are possible, and where they occur, profoundly impressive. However, the British did not leave India because they became compassionate; nor did white rule in South Africa end because whites became aware of their treatment of the black majority. They were defeated by predominantly non-violent strategies for change. Beneficiaries of violent arrangements will in general seek to retain their power, and they will oppose non-violent peacebuilders.

Non-violence itself has enemies

Despite these examples, we can observe a stereotype of peacebuilders that has wide currency. They are ‘soft-headed', ‘naive’, ‘ineffectual’, and ‘unrealistic’. More disingenuously, because it has the pretence of sympathy, they are ‘well-meaning but misguided’.

This seems initially curious, given that even with minimal resources (unlike their opponents), many of the greatest advances of 20th century were achieved through non-violence. It also takes place despite the failures of well resourced external military adventures in Afghanistan (repeatedly), Iraq, Libya, and elsewhere. Violent military intervention is rarely caricatured as naive. The hopelessly misconceived Vietnam war is not often described as ‘soft-headed’ or ‘ineffectual’. Why not?

I suggest that the reason for this mischaracterisation and discrepancy is in part the threat posed by non-violence itself. The enemies of non-violence control the means to profit from and use violence, but they do not control the ability of ordinary people to resist violence and respond together to challenge abuses of power non-violently. Non-violent power - ‘power with’ - belongs to us all. As such, it is a radical tool through which power can (at least in certain circumstances) be dramatically redistributed to the many, from the few. Non-violence itself is a threat to existing power relations. As a result, the tool of non-violence itself has enemies.

Beyond Galtung - a triangle of non-violence

It may be useful to apply Galtung’s principles to non-violence, exploring visible and invisible non-violence, and considering physical non-violence, structural non-violence, and cultural non-violence.

In relation to the first, visible non-violence is most easily apparent. Just as with physical violence, examples of visible non-violence abound, and can be easily observed. They might include the thoughtful facilitation of a meeting that enables quieter members of a group to be equally heard; the accompaniment of a neighbour facing hardship to authorities to present their case; participating in peaceful demonstrations that challenge injustice; or countless other personal or professional acts of kindness or resistance.

Invisible non-violence presents us with more to reflect upon. Structural non-violence might include decision-making structures that are inclusive and representative, egalitarian economic or political arrangements, and transparent or accountable mechanisms. Structures that nurture and reward compassion might go one step further.

In the field of structural violence and non-violence we can see battles being waged in many spheres. Wealthy interests for example may seek to hide the means of their enrichment, to avoid transparency in their dealings or responsibility to others through taxes. They may vehemently stand up for positions that oppose egalitarian arrangements or compassionate response. Politics is often used to preserve such interests, shore up or advance structural violence, or oppose non-violent arrangements.

John Rawls proposed that justice between people can be discerned by identifying arrangements that we would support, if we were ignorant of our place or position in that situation or society - as if we were behind a ‘veil of ignorance’. Our position in society would only be revealed after arrangements were settled. Such a tool is a powerful test for violence or non-violence. Under such a test, we can see that that justice and non-violence are not served by thousands of children held in the migrant camps of Calais, so as to prevent their migration from war zones and impoverished states?

Considering cultural or personal non-violence requires us to look more deeply. Unlike the structural machinery of our institutions and societies, religious, social and behavioural factors and attitudes are embedded within us. These promote both violent and non-violent responses from each of us. But at this level we are ourselves responsible, and often capable of turning to non-violence, and raising up the compassionate side of our nature. Many religious or reflective practices from different traditions explicitly encourage us to do so. (A and, as one would expect of all human institutions, many do not.)

My sense is that this personal and deep level of change is both the foundation for non-violent action, and also the level at which non-violence spreads between us. In the example of non-violent personal transformation by the woman in Rwanda that I described in the previous blog, the connection was powerful for all present. We listened to her story of personal change, and across cultures, nationalities and ethnic origins we were each held, moved and inspired. It was ‘power with’, and we all felt it.

Those of us who have been lucky enough to participate in non-violent demonstrations or activism will know this experience. In the room in Rwanda perhaps forty of us were affected. But the power no non-violence is not limited to small groups. Local, national and global movements have taken place founded upon that connection. I have seen it seeded successfully across East Africa, but we all appreciate its pivotal role in India at independence, South Africa at the end of apartheid, the US during the civil rights movement and the Vietnam war, Germany at the fall or the Berlin Wall, and Poland and elsewhere in Eastern Europe during the fall of the communism, and in the UK in the fight for the creation of democracy—the fight for votes for women. These examples are limited by my personal perspective - indeed, I expect that this experience unites us all.

So I suggest that the powerful tool of Galtung’s triangle, in revealing violence in its visible and invisible forms, should be matched by a comparable understanding of visible and invisible non-violence, equally common to human experience - relevant not only to understanding injustice, but also to addressing it - powerfully and repeatedly enabling people to change the course of history.

Taking up non-violent power - reflections from others

Marianne Williamson wrote:

‘Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine as children do. It's not just in some of us; it is in everyone. And as we let our own lights shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others’.

The power that Williamson is talking about is not ‘power over’, but ‘power with’. It is ‘our light not our darkness’ that she refers to, and it is a call to us all as peacebuilders to take up our power.

Acts of prominent non-violence speak to people, and power shifts again

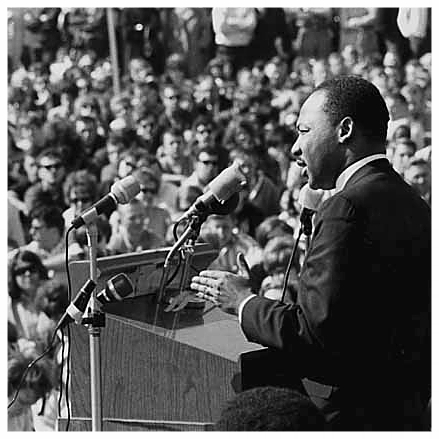

Peacebuilding is about challenging violence, and overcoming it with strategies that are more powerful. We can see that violent strategies and structures have been swept away by powerfully harnessing the non-violent power of thousands of individuals. And we can observe that, just as when physical violence commences there are shifts in the balance of power, so too is there a shift in the balance of power when non-violence is unleashed. Martin Luther King Jr. knew this when he wrote:

‘Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon. Indeed, it is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.’ Martin Luther King Jr., The Quest for Peace and Justice (1964)

Conclusion

This blog, and the accompanying trainings which will follow, is aimed at peacebuilders in all their guises, all of whom are in part at least intending to shift power and challenge violence. You will have in common either the experience or the aspiration, initially alone or with others, to act. This quote is for you:

‘Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back — concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth that ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans:

that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which none could have dreamed would have come their way.

Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, do it now. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.’

Often attributed to Goethe, that thought leads us to the third post on power, concerning leadership.

Post by Bryn Higgs from The Peacebuilding Practitioner.